Written by: Helen Chen and Edited: by Maria Cheung

In 2019, the United Nations General Assembly declared that 2021 was to be the International year of Creative Economy for Sustainable Development.

This meant an intention to center the importance of the creative industries’ contributions towards the UN sustainable development goals, on a global scale. This is a thriving sector that generates 3% of the world’s GDP, employs over 30 million people worldwide, and most importantly – is endlessly renewable and adaptable.

In Canada alone, creative entrepreneurs are projected to contribute 15% in GDP growth between 2017 and 2026 – we are in the midst of a creative revolution.

In many ways, the arts and cultural sector is the perfect environment to create productive cultural engagement on controversial topics not publicly discussed, yet privately experienced and dealt with by public health practitioners on a day to day basis. Whether it’s using a publicly-owned space to start an art-based awareness campaign, or creating sway for policy changes via creative advertising, we cannot deny its influence on culture and policy.

But what can public health practitioners, as individuals, gain from understanding more about the relationship between public health programming, policy, and the creative economy?

If we want to build strong relationships between these three groups, we must first gain a greater understanding of the key Canadian contributors and trends that drive them together. In this article, we will be focusing on activities within Edmonton, Toronto, and the province of Quebec as a whole.

Using Public Art As a Method for Advocacy

Public art, sometimes known as “creative placemaking”, is often described as a publicly funded, socially-engaged artistic practice that speaks to the time, place, and cultural conditions of when it was created.

Because of this, it has proven to be a smart, efficient way for nonprofits and grassroots movements to bring head turning awareness to sensitive topics, and improve the overall social fabric of a city.

A notable example of an installation with a strong public health context is the Edmonton Homelessness Memorial, commissioned by the Edmonton Coalition on Housing and Homelessness. The commissioned artists invited other local artists to contribute to the piece, by creating a unique tile that spoke to their experiences and thoughts on homelessness. The community engagement required to bring the work to life encapsulates a city’s collective emotions on a heavy subject topic.

In Toronto, there exists a thriving public art scene. In the last 50 years, over 700 installations have been built in the city, from 1967 to 2015. STEPS Public Art, a CRA registered charity, is one of the leading institutions in the area. They speak of taking an inclusive approach to public art, using it as a way to “challenge systemic inequities in public space, foster inclusive public art practices, and demonstrate the power of public art to reimagine equitably designed cities.” (Steps Public Art About page)

Ultimately, at its most socially influential, public art can contribute to public health policy discourse when it is rooted in community engagement, and amplifies the key issues of its surrounding community.

Art, Media and Public Health Policy

In 1979, Toronto set a precedent for anti-smoking by-laws in Canada by being the first city to ban smoking in retail stores, elevators, escalators and service line-ups.

What preceded it were years of massive policy reforms around tobacco distribution and consumption across Canada, eventually resulting in the 1997 federal Tobacco Act, which, among other decisions, put official age restrictions in place and standardized tobacco packaging.

At the same time, anti-smoking media campaigns grew in popularity across Canada, to help legitimize and accelerate smoking as a cultural taboo. Some notable ones include:

- Between 1970 – 1994 a set of animated short films were produced for children by the National Film Board of Canada, commissioned by the government, with themes that include self-denial, the nature of addiction, and the consequences of smoking.

- Stupid.ca: a government website launched in 2004 and advertised across TV and internet ads, with a humor-based approach to try and deter teens from smoking.

The Ontario Tobacco Research Unit reported in 2016 that Ontario smokers with any exposure to anti-smoking campaigns were 11% more likely to attempt quitting.

This speaks to the impact cultural producers have to change public perception on a topic, and ultimately gain more momentum for public health policy changes.

—

A more modern example of the art-policy intersection is the field of Arts-Based Health Research (ABHR) – an emerging field closely tied with Knowledge Translation that seeks to integrate creative art practices into the health research process.

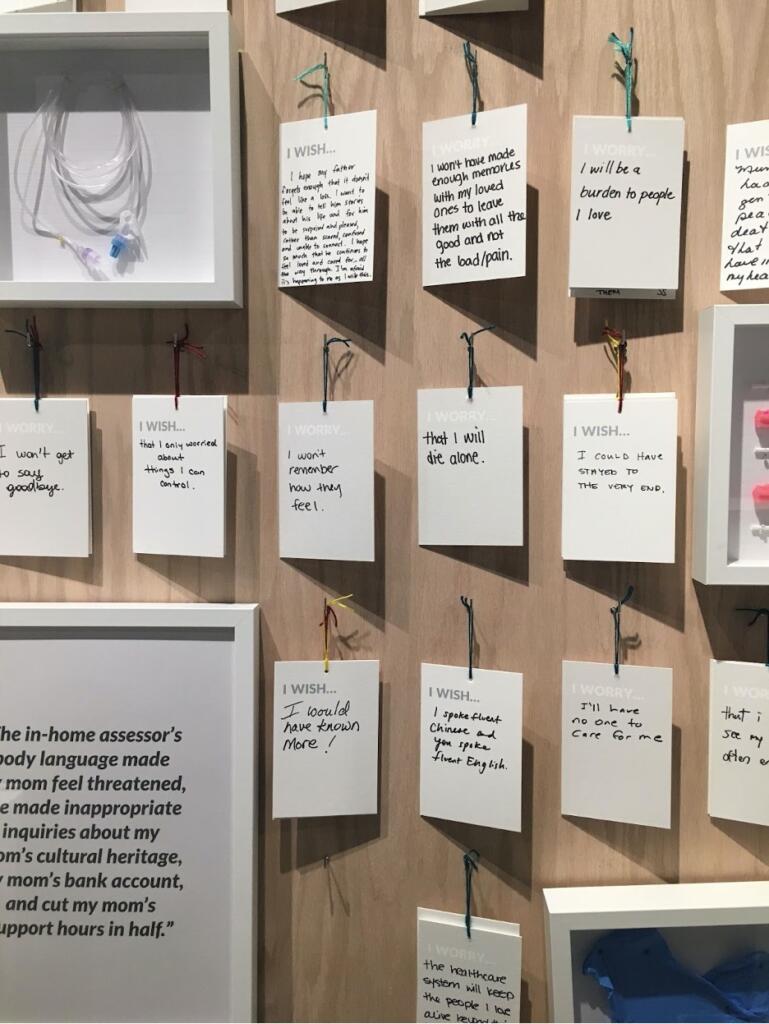

The research of Dr. Sarina Isenberg and Stephanie Saunders for design exhibition “Going Home to Die” is a part of that realm of exploration, where participatory public art is being piloted as a way to source and elicit broader perspectives on palliative care. The project was a collaboration with innovation designers Karen Oikonen and Kate Wilkes.

32 participants, including both patients and caregivers, were featured in the exhibit through quotes from Dr. Isenberg’s research about their emotions and experiences surrounding palliative care.

While the researchers were initially looking to validate palliative care process improvements through ABHR methods, they were instead able to elicit deeper and more authentic truths from installation participants than a formal interview or focus group would otherwise do.

The study ultimately revealed that for many patients, what truly matters at end of life care is the patient’s quality of relationships over traditional metrics of health service improvement, such as wait times to discharge from hospital to home.

Art-based methods of disseminating public health messages, whether for health promotion, cultural programming, or health policy research, create a strong indicator that art and media can play to complement and enhance public health interventions and strategies. Yet, the truth is that this is not currently recognized sector-wide as a valid strategy to achieve public health outcomes.

What’s Next for Public Art?

Despite Canada’s rich history as an art and cultural hub, there are some gaps in cultural production that have been identified by various Canadian researchers and policymakers.

What if we have been looking at the value of the arts from the wrong lens? Indeed, we have known the arts for it’s value in economics and aesthetics but perhaps that view is too narrow and our definition needs to be updated?

In Toronto, a noticeable lack of policy support in the industry was identified by OCAD University and the University of Toronto. Published in 2017, the Redefining Public Art in Toronto report describes Toronto as a city that lacks a public art master plan. At the time, it had not adjusted its own definition of what constitutes public art to fit with emergent art practices, and lacked policy tools to bring public art to ‘underserved areas’.

In response, Toronto has announced that 2021-2022 will be the city’s “Year of Public Art”, a set of programming activities under the 10-year Toronto Public Art Strategy umbrella.

Setting aside a 4.5 Million dollar budget in 2021, they will begin to broaden the scope of the public art definition in Toronto, a greater focus on Indigenous reconciliation within public art, and creating more space for public art to flourish in underserved communities.

By contrast, the same 2017 Toronto report notes that Quebec has historically been integrating public art more seamlessly into its municipal budgets than Toronto has, with positive ripple effects leading them to become Canada’s leader in public art.

The key factors in their success include, but are not limited to: having a strong annual budget, having a department solely dedicated to public art, increased engagement with the public, and encouraging modes of public art display outside of “permanent” and “temporary”.

Conclusion

In “Reshaping How We Understand the Impact of the Arts” by UK humanities researcher Geoffory Crossick, he states that the power of the arts is in its embodying of societal values such as taking risks, being in inquiry, creating space for nuances, and in addressing complexities.

Moreover, he claims that there is a transformative energy made possible in our human experience (we would add perhaps in collective healing and social progress) behind the process of all those involved in the making of the art, in this case for example in the citizens, patients, researchers, service providers, and city planners involved.

The true value then lies in the process, and in some cases may be seen as even more valuable than the artworks themselves.

Now, imagine what would be possible in a society, and a public health system designed around these values? We would argue that embodying these social values is needed today, more than ever.

Further Reading

Reimagining University Avenue: a public art + public health initiative

PULSE TOPOLOGY: a Toronto immersive interactive exhibition under the Gardiner Bridge

Research – Expressive Freedom and Tobacco Advertising: A Canadian Perspective

Steps Public Art – St. James Town Cultural Plan (2020)

About the Authors

Maria Cheung

Maria is a Public Health, Policy Professional and the founder of Taboo Health bringing over a decade of experience in government and academia. She is a policy maker in acute care and a public health nerd (MPH) passionate about health communications, health promotion and systems design with the creative sector to advance public discourse and cultivate community healing. She is endlessly fascinated by the beautiful, awkward and uncomfortable spaces felt in between the black and white. When not nerding out about public health, art and culture, she is adventuring on a canoe camping trip, on her bicycle for multi day tours, backcountry skiing, or dancing up a salsa and bachata storm.

Helen Chen

Helen is a new media artist and graphic designer, currently working on her BFA at Ryerson University. Over the last 3 years, she has worked with numerous organizations to help solve a range of communication + visual design problems, including nonprofit data collection, fashion sustainability, and most recently, with Taboo Health to help define and visualize relationships between the public health sector and fine arts.

Being extensively involved in experiential art + design communities as a creator, she understands the importance of using art as a vehicle to create safe public spaces for difficult, yet necessary conversations.