This is a 3-part series written by Madison Moon and Alice Silva, who are both Infection Control Practitioners – read part 1 here. Part 2 is written by Madison.

I discovered infection control while focusing my MPH studies on biostatistics with the initial goal of developing and maintaining robust data management and validation strategies for multivariate meta-analysis in clinical trials. My program concluded with a capstone research practicum which involved community organizations hosting and facilitating research studies related to a student’s specialized interest. I applied to complete my practicum with the Infection Prevention and Control (IPAC) department at Joseph Brant Hospital in Burlington, Ontario, Canada with hopes of conducting a retrospective cohort review identifying community susceptibility patterns for antibiotic resistant organisms.

My first day with the IPAC department was intense – setting me up with a computer was the least of their problems. They were down a staff member and an ongoing investigation was taking place into a patient’s acquisition of Clostridium Difficile. Determination of this infection’s clinical impact on a patient and where the patient acquired the infection (i.e. in the hospital/another hospital/or the community) was crucial to both the next control steps and what messaging would be relayed to the hospital’s senior leadership team. C. Difficile represented not only a concerning infection transmission event to this team (albeit a common infection occurring predictably at ~6 cases per 10,000 patient days in Ontario, Canada), but a matter that needed careful presentation due to its history in this hospital.

I spent my first day following the department’s manager and physician as they provided education to the nursing unit and charted contributing factors. This included a review of charted variables like the patient’s intake of nutritional drinks known to cause diarrhea, notes from stays in other facilities, antibiotic usage, and contact tracing to previous occupants of the room/records of room cleaning with bleach. As well, the IPAC team stayed close to the unit all day to gather observational variables including the nursing unit’s practice of appropriate isolation measures and hand hygiene. They also audited the handling of bedside commodes from patient rooms to a macerator device in the dirty utility room (later implicated in another case as a likely route of C. Difficile spore contamination).

I had no context prior to this experience to understand that the infection control department’s role involved such an active investigative approach and response. I emailed my advisor after my first week with this department with a new proposal for my capstone research project that would bring me closer to the frontline of infection control practice.

Over the next 4 months, I completed a prospective analysis of patient navigation and bed flow as it is impacted by patients isolated for infectious diseases. I became obsessed with the exploration of variables leading to infection transmission events in hospital settings over the course of this practicum and completion of a subsequent online certificate in Infection Control (at Queen’s University). I think anyone who’s explored cohort studies in public health research would be intrigued by the level of information and controls available for surveillance and monitoring in healthcare settings. In many ways, I have found that the investigative work involved in Infection Control represents one of the purest forms of epidemiology; contained populations with all major health concerns, laboratory analysis, and even pharmaceutical/dietary intake charted for review. These readily available analytic controls charted in electronic medical records for inpatients are often impossible to attain even in closely monitored clinical trials and case-control studies in the wider public health realm.

In my first professional role in infection control, I covered a procedural role of managing patient flow for the hospital’s colonized antibiotic resistant organism (ARO) portfolio. AROs are often the largest contributor to a hospital’s patient isolation burden and a notable barrier to achieving optimal patient flow in hospitals with limited private room availability (isolated patients ideally do not share rooms with other patients). AROs that have colonized on a patient’s skin are often treated clinically via bioburden reduction therapy; but require three swabs (depending on organism, through rectal or nasal/axilla/perineum) yielding negative results to discontinue precautions. Collection of swabs additionally is required to be spaced at least a week from the last. Even when patients are discharged from a facility and return during/following decolonization therapy, they remain on contact isolation until these criteria (three negative swabs spaced at least a week apart) can be obtained. Additionally, when cross-sectional or retrospective contact tracing yields potential exposures to patients with lab-confirmed positives for antimicrobial resistant organisms (e.g. patient was a roommate of an ARO positive patient prior to identification of a positive result), the same three swab/three week protocol is used to verifying whether a transmission event had occurred.

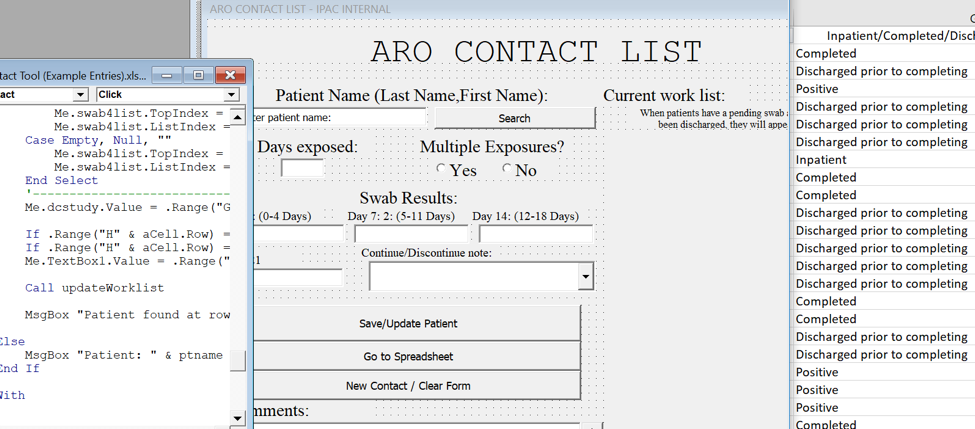

To facilitate record-keeping and scheduling of swabs/result tracking, I was provided a Microsoft Excel-based line list of all patients undergoing bioburden reduction therapies. This spreadsheet acts as a repository of notes from the electronic medical record supplemented by faxed laboratory results for patients with positive results alongside potentially exposed contacts of all antimicrobial resistant organisms currently tracked by the hospital (Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcal Aureus [MRSA], Extended-Spectrum Beta Lactamase [ESBL], Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae [CRE], and Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococcus [VRE]). The expectation was that the practitioner reviews this summative list, orders swabs on appropriate follow-up dates, and updates results as microbiological results become available.

I knew there were better ways to program this record sheet from work I had completed in clinical trial data management. In this role I had ensured appropriate follow-up scheduling and data validation processes without losing track of ongoing patients. So, I spent some time automating myself out of a job by bringing in data validation measures, automated calendars with notification reminders, and a propagated dashboard of current cases for review:

Since this experience, I have found many ways to integrate my experience with biostatistics and further studies in infectious disease surveillance (i.e. continuing education that has been influenced greatly by my newly discovered obsession with infection control in healthcare settings). My current position at Princess Margaret Cancer Centre provides daily opportunities to advise care practice in a clinical trial environments, provide clinical risk assessment and control of infectious diseases for an immunocompromised population, and assist in conducting surveillance and rapid identification of communicable disease cases in the greater public health realm through my work in ambulatory clinics.

Read Part 1 here.

Read Part 3 here.